What is usability? It's the study of making things usable, or, as you may know from filling out your taxes, backing up your computer (Mac users don't count), or even gassing up a different car, we all must do things that can be unclear at times.

Usability is not an entirely new concept but is finally becoming more mainstream: if things were designed with the end user in mind, how much easier could they be? How much money and time could be saved?

It's easier to find a parking spot at BWI now that green lights indicate open spaces. Universities that pour walkways before researching paths spend more reconstructing trampled lawns as students make preferred shortcuts known. Clear road signs can prevent existential crises, like what must happen to literally *everyone* at the below intersection:

A usable world is simply a better one.

The workshop, called "Introduction to Human-Centered Design" ("human-centered" is the preferred nomenclature in the field) was mainly an overview of the process: how to gather data, compile ideas, and make and test prototypes, and why it works to do it in a particular way (inquiry / prototype / test / repeat).

Problem-solving starts with identifying the problem. What is the issue? You may think it's one thing but until you talk to the people who experience it, you can't know for sure.

For example, chronically running late may appear to be a traffic issue but may actually be a planning one. Poor sleep quality may not be the mattress after all but instead too much light or noise at night.

In order to find out, you have to dig.

The class walked us through the process and had us leap almost immediately into the "field" to begin practicing our new interviewing skills. We used a generic question that could apply to anyone just for the sake of learning the process. We asked, "Is there anything that gets in the way of your health? Or of you being as healthy as you want?" (In a real case scenario, the questions would be tailored to the field.)

We roamed the building for people to interview. Not having been telemarketers in a previous lives made us shy approaching strangers but the class instructor gave us tips. "Approach gently and explain who you are and what you're doing. When you start hearing the same answers over and over, you'll know you've amassed enough data."

People eyed us suspiciously at first but when they realized we weren't collecting money, out poured the litany of health destroyers. They came in the form of many things: long commute, expensive food (broccoli costs more than ramen), picky children, gyms that were too far away and days that started before dawn. Our subjects looked weary just recounting all the things.

We dug deeper using techniques taught in the class, such as the "5 Whys" (a strategy no doubt borne from a toddler) where you ask "why" multiple times, or encourage a story or ask for a visual.

Answers did start to get repetitive and we found that the common thread was time. People weren't taking as much care of their health as they wanted because they didn't have enough time.

Next step: now what? People need more time, how could we make that happen?

Our team rejoined and after a brainstorming session that nixed moving to Venus just to have 5,000 more hours in a day, we developed possible "prototypes" -- actual, physical implementations to show people -- and marched back into the field to see how they'd fare.

We interviewed more people but this time sporting a poster and miniature booklet as visual aids to illustrate our ideas: policies to improve work/life balance, like telecommuting, and utopia where folks could live near their work. After all, some folks spent 4 hours on the road every day. That's horrendous.

Other teams in our class came up with different ideas for improving health, like tools for information dissemination, apps to make exercise easier, and even a snazzy business plan to offer healthy food on the metro so travelers could save time eating breakfast on their commutes.

During this secondary idea-sharing stage, teams are encouraged to ask each other: what would you add to this idea? What questions do you have? What else should be considered? (We wondered, who would clean up the extra trash? Would we lose our seats if we got up to purchase a banana?) Input refines the idea.

Design thinking is iterative, meaning it can go around and around in loops. You start with the question, gather data, test your idea, ask more questions, test more ideas, lather, rinse, repeat.

The field combines elements of engineering and the social sciences: engineering because of the prototypes, and social sciences because of the interviewing.

Marry the two and you have inquiry designing prototypes, not designing before you find out exactly how a thing might be used.

It's also important to note that how people say they will use something isn't always how they will *actually* use it, as anyone who's ever bought a treadmill will know. Observation will always reveal the most reliable data.

We can't wait until the next class!

If you're interested in learning more, see:

- Why Human-Centered Design Matters (from Wired magazine)

- IDEO Design Kit (includes tools for the inquiry process)

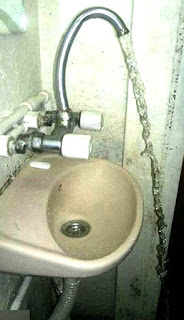

Examples of Usability Fails:

|

| Um... |

|

| The cone of shame: healing aid or diet platform? |

|

| Now imagine you're rushing to your doctor's office... |

|

| Don't assume it's usable until you test it first! |

|

| Finally, an honest pop-up. |

No comments:

Post a Comment